The Autopsy of Attrition: Systemic Failure Modes and Insolvency Timelines in the United States Household Goods Moving Industry

Executive Summary

The United States household goods (HHG) moving industry, a critical logistical artery of the residential real estate market, operates within a notoriously volatile economic framework characterized by low barriers to entry and high barriers to sustained profitability. Despite generating annual revenues exceeding $22 billion and facilitating the relocation of nearly 26 million Americans annually, the sector is plagued by a severe rate of business attrition. Comprehensive industry data indicates that approximately 40% of moving businesses fail within their first three years of operation , with an annual closure rate of established businesses hovering between 2% and 3.5%.

The years 2023 through 2025 have proven particularly lethal for small-to-mid-sized operators. Confronted by a "stagflationary" environment of suppressed housing turnover—driven by elevated interest rates—and skyrocketing operational costs, the industry has undergone a harsh Darwinian correction. In 2023 alone, fewer than half (40%) of moving companies met their revenue goals, and one-third were forced to leverage high-interest debt instruments to maintain solvency. The divergence between "best-in-class" operators achieving net margins of 20%+ and the vast majority struggling at "survival margins" of 7% or less has never been more pronounced.

This report provides an exhaustive forensic examination of the mechanisms of failure in the relocation sector. It dissects the financial physiology of the moving firm, analyzes the operational pathologies that precede insolvency, and maps the precise legal and regulatory timelines of collapse—from the initial capitalization errors to the final revocation of Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) authority and Chapter 7 liquidation.

Part I: The Macroeconomic Crucible and Market Fragility

To understand the mechanics of individual firm failure, one must first analyze the hostile external environment in which these entities operate. The moving industry is a derived-demand sector, its fortunes inextricably tethered to the velocity of the national housing market and the broader macroeconomic climate.

1.1 The Post-Pandemic Correction and Demand Suppression

The period spanning 2020 to 2021 represented a "Gold Rush" era for the moving industry, driven by pandemic-induced migration and remote work flexibility. Search volumes for moving services peaked in 2021, showing a 74% increase over 2019 levels. This demand surge masked fundamental operational weaknesses in many firms, allowing inefficient operators to survive on volume alone.

However, the subsequent correction revealed the sector's extreme sensitivity to monetary policy. As the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates to combat inflation, the housing market froze. Homeowners holding mortgages with historically low rates (2-3%) became unwilling to sell and finance new properties at rates approaching 7-8%, creating a "lock-in" effect that decimated existing home sales—the primary feeder for the moving industry.

By 2023, the impact was systemic:

Revenue Stagnation: 32% of moving businesses reported minimal revenue change (-10% to +10%), while a significant cohort saw deep contractions.

Search Volume Decline: Consumer interest normalized downward, exposing the overcapacity built up during the boom years.

Negative Sentiment: 76% of moving company owners explicitly cited rising interest rates as a primary negative driver for their business.

This demand shock was not merely a cyclical downturn but a structural realignment. Companies that had scaled their fixed costs—leasing additional trucks, expanding warehouse footprints, and hiring administrative staff—based on 2021 revenue projections found themselves over-leveraged in a contracting market.

1.2 The Inflationary Vice: Decoupling of Cost and Price

While demand softened, the cost of service delivery accelerated, creating a margin squeeze that many firms could not survive. Between 2020 and 2025, underlying operational costs for transportation service providers rose by 30% to 80% across critical categories.

Table 1.1: Inflationary Impact on Key Cost Drivers (2020–2025)

Cost CategoryEstimated IncreaseOperational ImpactDiesel FuelHigh VolatilityErodes margins on fixed-price long-distance moves; necessitates frequent tariff surcharge updates.Labor (Wages)+20–30%

Severe shortage of CDL drivers and qualified movers forces wage hikes to retain staff and combat turnover.

Equipment (Fleet)+30–50%Supply chain shortages drove up the cost of new trucks and parts, increasing lease payments and maintenance outlays.Insurance+10–20% annually

Hardening markets in auto liability and workers' compensation drive premiums significantly higher.

General Overhead~25% (CPI)

Rent, utilities, and administrative salaries rose alongside the Consumer Price Index.

The lethal mechanism here is the "pricing lag." Interstate moving tariffs and binding estimates often lock in pricing weeks or months in advance of the actual move. In a rapidly inflationary environment, a quote provided in April for a July move might become unprofitable by the time the service is rendered due to spikes in fuel or labor costs. Companies lacking the sophistication to dynamically adjust their pricing models or enforce fuel surcharges essentially subsidized their customers' relocations, bleeding equity with every mile driven.

1.3 The Seasonality Trap: The "Killing Season" Phenomenon

The most distinct structural threat to moving company solvency is the extreme seasonality of the business cycle. The industry operates on a feast-or-famine rhythm that punishes poor cash flow management with swift insolvency.

Data indicates that approximately 60% of all relocations occur during the "peak season" window of May through August. During these months, utilization rates for trucks and labor are high, and cash inflow is substantial. However, this is immediately followed by the "trough" or "killing season" spanning November to March, where volume can drop by 50% or more.

The Liquidity Trap

The failure mechanism associated with seasonality is behavioral and accounting-based. Inexperienced owners frequently mistake the cash surplus of July for net profit. Failing to account for the deferred maintenance, upcoming insurance renewals, and the inevitable winter revenue drought, they deplete these reserves on owner draws, bonuses, or ill-timed capital expenditures.

When January arrives, revenue often fails to cover fixed operating costs (lease payments, insurance premiums, warehouse rent, salaried payroll). Without a "drip account" or substantial cash reserves to bridge this gap, the business faces a liquidity crisis.

Predatory Financing: To survive the winter of 2023, 33% of movers turned to lines of credit or cash advances. Merchant Cash Advances (MCAs), which sweep a percentage of daily credit card sales, are particularly pernicious. They reduce the effective margin of future work, creating a debt spiral that often leads to bankruptcy before the next peak season begins.

Part II: The Financial Physiology of Failure

To understand why 40% of companies fail in their first three years, we must look beyond the macroeconomics and examine the internal financial health of the typical failing firm. The difference between a solvent mover and a bankrupt one is often found in the granularity of their Profit & Loss (P&L) management.

2.1 The "Survival Margin" vs. "Success Margin"

Industry benchmarking for 2025 has established clear delineation lines for financial viability.

The Danger Zone (<7% Net Margin): A net profit margin of 7% is identified as "barely survival". At this level, the company has zero resilience. A single catastrophic event—such as a blown transmission ($15,000 cost), a denied insurance claim, or a lawsuit—can exceed the entire year's retained earnings.

The Target Zone (>20% Net Margin): Best-in-class operators achieve margins exceeding 20% by rigorously tracking KPIs and diversifying revenue streams.

The failure to track these metrics is widespread. A staggering 41% of moving company owners do not track KPIs at all. This financial blindness means they cannot identify which service lines (local moving, long-distance, packing, storage) are profitable and which are bleeding cash. They often "buy revenue" by taking unprofitable jobs just to keep trucks moving, accelerating their descent into insolvency.

2.2 The Cost of Compliance and Insurance Burden

Insurance is not merely a fixed cost in the moving industry; it is a dynamic variable that acts as a "competence tax." The cost of insuring a moving fleet has become one of the primary drivers of insolvency.

The Insurance Stack

A compliant moving company must carry a complex stack of policies. In 2024/2025, the average monthly costs for a single truck's coverage were estimated as follows:

Commercial Auto Liability: ~$876 per month (varies by fleet size and safety record).

General Liability: ~$120 per month.

Workers' Compensation: ~$755 per month.

Cargo/Warehouse Legal Liability: ~$0.60 per pound or variable based on valuation coverage.

For a small fleet of five trucks, insurance premiums alone can exceed $10,000 per month.

The EMR Multiplier Effect

The Workers' Compensation Experience Modification Rate (EMR) is a critical lever. The industry average EMR is 1.0. If a moving company has poor safety practices—leading to frequent back injuries or slips—their EMR rises.

The Impact: A company with an EMR of 1.25 pays 25% more for its workers' compensation insurance than a competitor with an EMR of 1.0.

The Death Spiral: This creates a structural competitive disadvantage. The unsafe company has higher costs, forcing them to either charge higher prices (losing volume) or accept lower margins (losing viability). High claims stay on the record for three years, meaning a single bad season can handicap a company's profitability for 36 months.

2.3 Operating Authority and Tariff Costs

Beyond insurance, the administrative burden of legality is significant.

Authority Costs: Obtaining a DOT number is free, but an MC (Motor Carrier) number costs $300 per authority type (e.g., Common Carrier of Household Goods). Reinstating a revoked authority costs $80.

Tariff Publishing: Interstate movers are legally required to publish a tariff (a list of rates and rules) and make it available to consumers. Failure to do so, or charging rates that deviate from the tariff (random discounting), is a violation of 49 USC § 13702 and can incur civil penalties of up to $100,000 per violation.

Legal Fees: Many failing companies attempt to save money by writing their own tariffs or contracts, leading to non-compliant documentation that fails to protect them in court during cargo claims disputes.

Part III: Operational Pathology and the Mechanics of Breakdown

Financial failure is rarely the result of bad math alone; it is almost always the lagging indicator of operational failure. The specific operational pathologies that plague moving companies are consistent and predictable.

3.1 The "Technician's Trap" and Scaling Failures

A predominant archetype of failure is the "Technician Entrepreneur"—an individual who was an excellent mover or driver but lacks executive management skills.

The Delegation Failure: As the company grows from 1-2 trucks to 5+, the owner can no longer be present on job sites. Without robust standard operating procedures (SOPs) and training programs, the quality of service dilutes.

The Scaling Gap: Scaling is a distinct skill from moving. Failing owners often expand their fleet before expanding their back-office infrastructure. They add trucks but fail to add dispatchers, claims managers, or sales staff. This leads to administrative chaos, missed calls, scheduling errors, and a collapse in customer service quality.

3.2 The Labor Turnover Crisis

The moving industry is labor-intensive and physically demanding. The ability to recruit, train, and retain reliable labor is the single biggest operational differentiator.

High Turnover: The industry faces turnover rates similar to the long-haul trucking sector, which can reach 94% annually.

The Cost of Churn: Constant turnover creates a perpetual training deficit. New, inexperienced movers are statistically more likely to cause property damage and personal injury.

The "Warm Body" Problem: Desperate to fill trucks during peak season, failing companies often lower hiring standards, skipping background checks or drug tests. This increases the risk of theft, "no-shows," and rogue behavior by crews, which in turn leads to lawsuits and insurance claims.

3.3 The Claims Death Spiral

Cargo claims are the "check engine light" of a moving company.

Frequency vs. Severity: While occasional damage is inevitable (industry average claim ratios can be tracked), a spike in claims frequency indicates a systemic failure in training or packing materials quality.

The Financial Hit: Most movers operate with a deductible (e.g., $1,000 or $2,500) on their cargo insurance. If a company has frequent small claims (e.g., $500 for a scratched table), they often pay out of pocket to avoid hiking their insurance rates.

Cash Drain: These out-of-pocket settlements drain working capital. If the company stops paying claims to save cash, customers file complaints with the Better Business Bureau (BBB) and FMCSA. This triggers regulatory scrutiny and destroys the company's online reputation, increasing the cost of customer acquisition.

3.4 Office Move Specifics: The Commercial Failure Mode

Companies attempting to diversify into commercial/office moving often fail due to the higher complexity and stakes.

The Downtime Risk: Commercial clients demand zero downtime. A failure to execute an office move on time (e.g., over a weekend) can result in massive liability for the client's lost business productivity.

Logistical Hurdles: Common failure points include elevator conflicts (failing to book freight elevators), Certificate of Insurance (COI) rejections by building management, and IT disconnect/reconnect failures. A single botched office move can result in a lawsuit that bankrupts a small residential carrier ill-equipped for the commercial sector.

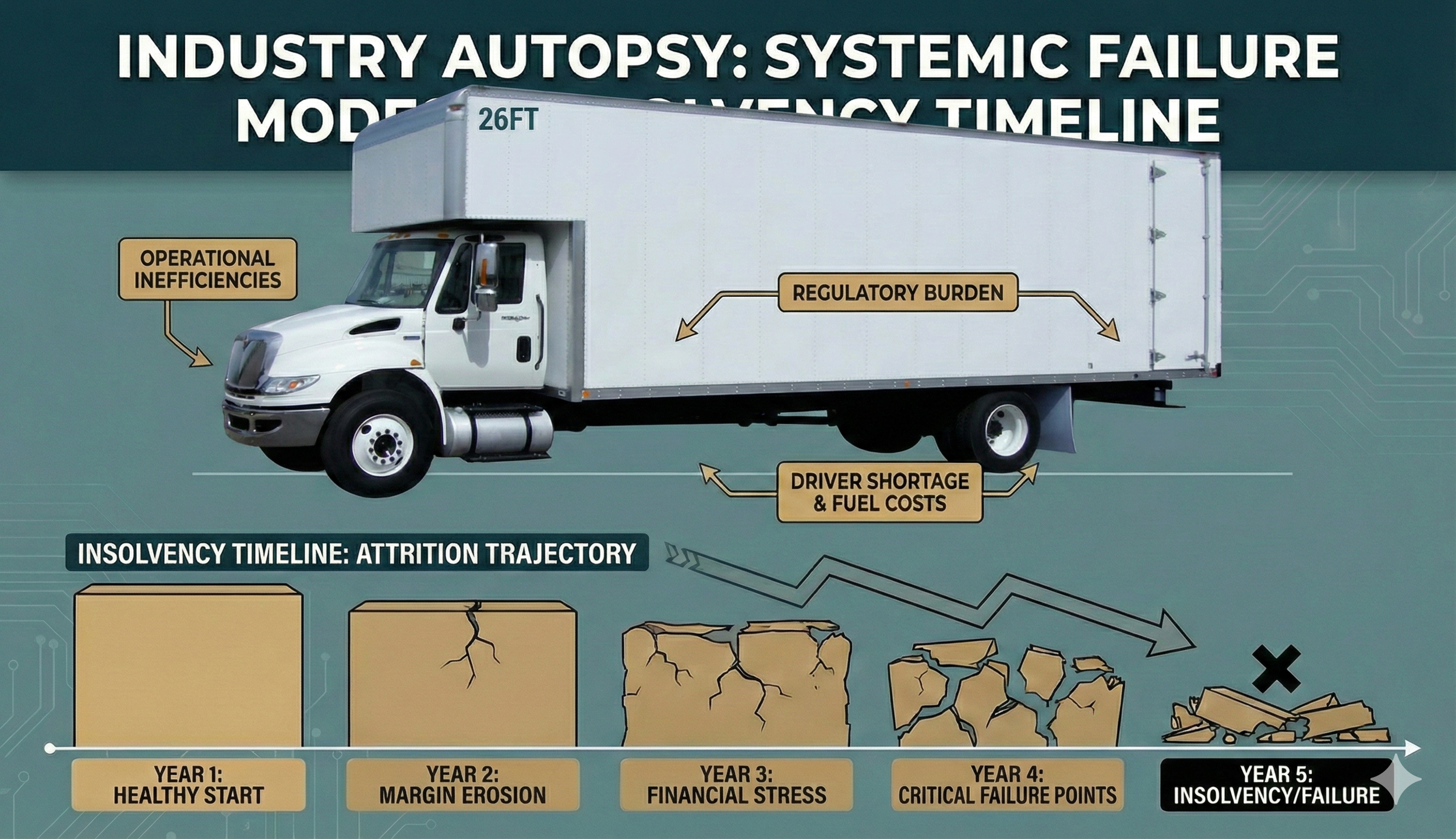

Part IV: The Timeline of Collapse

Insolvency in the moving industry is rarely an instantaneous event. It follows a predictable chronology, a "slow-motion car crash" that unfolds over 12 to 36 months. We can categorize the lifecycle of failure into four distinct phases.

Phase 1: The Incubation of Error (Months 1–18)

Status: Operational but Fragile

The business is launched, often with undercapitalization. The owner purchases used trucks (10+ years old) to save money, planting a "maintenance time bomb."

The Pricing Sin: Desperate for volume, the new company underbids established competitors. They fail to account for the full burden of overhead in their hourly rates.

The Accounting Void: Personal and business finances are commingled. The owner uses the business account to pay personal bills. There is no distinction between "deposit cash" (liability) and "earned revenue" (asset).

The First Winter: The business hits its first seasonal trough. Cash reserves are nonexistent. The owner uses personal credit cards to cover fuel and payroll, establishing a debt burden that will never be fully serviced.

Phase 2: The Stumble and Debt Trap (Months 18–30)

Status: Distressed

The company has survived the first year but is not profitable. The owner interprets the lack of cash as a "volume problem" rather than a "margin problem" and attempts to scale out of the hole.

Unprofitable Growth: New trucks are leased or financed. The fleet grows, but administrative capacity does not.

The MCA Catalyst: To fund the expansion or survive the second winter, the owner takes a Merchant Cash Advance (MCA). This predatory lending product advances cash against future credit card sales.

The Impact: The lender sweeps a fixed percentage (e.g., 15-20%) of daily revenue. This effectively destroys the margin on every job before the truck even leaves the yard.

The Cycle: To cover the cash shortfall caused by the daily sweeps, the owner takes a second position MCA, then a third. The business is now working solely to service debt.

Phase 3: The Death Spiral (The Final 6–12 Months)

Status: Insolvent

The business is operationally dysfunctional and financially hollow.

The Deposit Ponzi: The company begins using deposits from future moves (booked for next month) to pay for today's payroll and fuel. This is the point of no return.

Insurance Games: To save cash, the owner delays insurance payments. The policy enters a grace period.

Maintenance Triage: Preventive maintenance is abandoned. Trucks break down frequently, leading to rental truck costs and missed pickups.

Reputation Collapse: The company's Google rating drops below 3.5 stars. Lead generation costs skyrocket as discerning customers avoid the brand. The company is forced to buy low-quality leads, attracting price-sensitive customers who are more likely to complain.

Phase 4: The Terminal Event (Revocation and Liquidation)

Status: Defunct

The end is triggered by a specific event that the fragile company cannot absorb.

The Insurance Cancellation: The carrier misses a premium payment. The insurance provider files a BMC-35 Notice of Cancellation with the FMCSA.

The 30-Day Clock: The FMCSA issues a "Pending Revocation" status. The carrier has 30 days to file new proof of insurance.

Revocation: On Day 31, Operating Authority is revoked. The company can no longer legally operate interstate.

The Lawsuit: A major accident or "hostage load" complaint triggers a lawsuit or Attorney General investigation. Legal fees are immediate and insurmountable.

Bankruptcy: The owner files for Chapter 7 liquidation.

Asset Seizure: Secured creditors (banks) repossess the fleet.

The Void: Unsecured creditors (customers with damage claims, employees with unpaid wages) typically receive nothing.

Part V: The Rogue Mover Phenomenon

It is critical to distinguish between the failure of a legitimate business due to incompetence and the "failure" of a rogue operator due to regulatory enforcement. Rogue movers operate on a model of fraud and regulatory arbitrage.

5.1 The Mechanics of Fraud

Rogue movers exploit the customer's lack of knowledge.

The Lowball: They provide non-binding estimates over the phone without a visual survey, quoting prices 40-50% below market rates.

The Hostage Load: On moving day, after the truck is loaded, the price is hiked based on "unexpected cubic footage" or "packing fees." The mover demands cash before delivery. This practice is federally illegal but common among rogues.

Cost Avoidance: Rogue movers artificially suppress costs by carrying personal auto insurance instead of commercial, paying workers under the table to avoid workers' comp premiums, and ignoring vehicle maintenance.

5.2 The Reincarnation Cycle (Chameleon Carriers)

Rogue movers rarely "fail" in the traditional sense; they "molt."

Burn and Churn: A rogue entity operates for 12-18 months, accumulating "F" ratings with the BBB and consumer complaints.

Voluntary Revocation: Before the FMCSA can shut them down involuntarily, the operators voluntarily revoke their authority.

Rebirth: They register a new LLC, often using a relative's name or a "straw man" owner. They obtain a new DOT number and MC number, essentially resetting their safety score and reputation.

FMCSA Countermeasures: The FMCSA has intensified efforts to identify these "chameleon carriers" by cross-referencing phone numbers, addresses, and officer names in the registration database. New rules allow the agency to withhold registration if an applicant fails to disclose relationships with prior revoked carriers.

5.3 Operation Safe Move and Enforcement

State Attorneys General also play a role in the timeline of rogue failures. "Operation Safe Move" in New Jersey serves as a case study:

The Sting: Undercover investigators posed as customers hiring movers from online ads.

The Bust: 23 unlicensed movers were caught.

The Penalties: Civil penalties of $5,000 for first-time offenders and $10,000 for repeat offenders were assessed. For a fly-by-night operator, a $10,000 fine is often a terminal event, prompting them to abandon the LLC and disappear.

Part VI: Regulatory and Legal Mechanics of Shutdown

The dissolution of a moving company is heavily bureaucratic.

6.1 FMCSA Authority Revocation Protocol

The loss of Operating Authority is the functional death of an interstate mover.

Trigger: Insurance cancellation or safety rating downgrade (Unsatisfactory).

Notification: The FMCSA sends a warning letter three days after receiving the insurance cancellation notice.

The Window: The carrier has exactly 30 days to file a BMC-91X (Proof of Liability Insurance) or BMC-34 (Proof of Cargo Insurance).

Revocation: If the filing is not received, the authority status changes to "Inactive/Revoked."

Reinstatement: To revive the company, the owner must pay an $80 reinstatement fee and file the necessary insurance forms. However, operating during the revocation period subjects the carrier to massive fines and vehicle impoundment.

6.2 Bankruptcy Proceedings

When informal dissolution is not possible due to debt loads, bankruptcy is the legal path.

Chapter 7 (Liquidation): The most common route for small movers.

The Automatic Stay: Filing halts all collection actions and lawsuits immediately.

The Trustee: A court-appointed trustee sells off any unencumbered assets. However, in most moving company failures, the trucks are leased or heavily financed, leaving little equity for distribution.

The Discharge: Debts are discharged roughly 90 days after filing, provided no fraud is detected.

Chapter 11 (Reorganization): Rare for this sector due to high legal costs. It requires a viable plan to repay creditors over 3-5 years while keeping the business running. This is typically only an option for larger van lines with significant assets and brand equity to protect.

Part VII: Strategic Remediation and Future Outlook

While the failure timeline is grim, it highlights the specific traits of survivors. The "best-in-class" operators who survived the 2023-2025 downturn share common characteristics that serve as a blueprint for viability.

7.1 Tech-Enabled Resilience

Survivors have moved away from manual processes.

Virtual Surveys: Using AI-powered video survey tools (e.g., Yembo) allows for highly accurate volume estimation without the cost of sending a salesperson to the home. This prevents the "underestimation" errors that destroy margins.

CRM Integration: Sophisticated CRM systems (e.g., SmartMoving, Supermove) automate follow-ups and lead management, ensuring that expensive leads are not wasted.

7.2 Diversification as a Hedge

Successful firms break the seasonality trap by diversifying revenue.

Storage: Secure storage generates Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) that helps cover fixed costs during the winter months.

Commercial Moving: Corporate relocations are often less seasonal than residential moves and provide higher margins, though they require higher operational discipline.

7.3 Financial Discipline

The survivors of the 2025 shakeout are those who manage their balance sheets with conservatism.

The Drip Account: Allocating a percentage of summer revenue into a dedicated reserve account to fund winter operations.

Debt Avoidance: Avoiding MCAs at all costs and relying on traditional lines of credit only for true capital expansion, not operational shortfalls.

Conclusion

The failure of a moving company is rarely an accident; it is a systemic outcome of specific inputs: undercapitalization, pricing ignorance, and operational fragility. The timeline is predictable, moving from the initial accounting errors of the first year to the debt-fueled desperation of the second and third.

While the macroeconomic headwinds of the 2020s—inflation, interest rates, and labor shortages—have accelerated the demise of weaker players, they have also clarified the requirements for success. The moving company of the future is not merely a trucking operation; it is a data-driven logistics firm that treats compliance, safety, and financial planning as core competencies equal to the physical act of moving furniture. For those who fail to make this transition, the timeline from inception to insolvency remains brutally short.